“‘The fault…..is not in our stars, but in ourselves…..’ -Shakespeare

Our story deals with psychoanalysis, the method by which modern science treats the emotional problems of the sane.

The analyst seeks only to induce the patient to talk about his hidden problems, to open the locked doors of his mind.

Once the complexes that have been disturbing the patient are uncovered and interpreted, the illness and confusion disappear…..and the devils of unreason are driven from the human soul.”

So reads the opening title cards for Spellbound, Hitchcock’s noir-thriller set in the world of psychoanalysis. The project came about because producer David O. Selznick had started going to therapy, had a positive experience, and thought Hitchcock - who was still under contract to him at the time - should make a picture about that. (I’m reminded of the 30 Rock bit where Jack Donaghy sits in on the writer’s room and pitches Dilbert.)

It says a lot about public perception of the relatively new practice (at least in the United States) of mental health treatment in 1945 that a movie about psychoanalysis was called Spellbound. While that title card sequence suggests a social issues movie in the vein of Stanley Kramer, Spellbound is not a movie that realistically depicts mental health disorders or their treatment any more so than Psycho does. It was, however, one of the first Hollywood movies to depict the practice and present its ideas with some seriousness. And, for Hitchcock, Spellbound is his first portrayal of a character searching their subconscious for repressed memories in order to confront their neuroses and fears - a key Freudian concept he’d explore in more fully realized ways later with Vertigo and Marnie. This existed under the surface in prior work (like Suspicion), but never quite so explicitly or distinctly articulated.

The story begins at Green Manors, a Vermont mental hospital, where we’re introduced to Dr. Constance Petersen (Ingrid Bergman, in her first collaboration with Hitchcock), a reserved psychoanalyst working under the hospital’s outgoing director, Dr. Murchsion (Leo G. Carroll, of Rebecca and Suspicion). Murchison, who’s being forced into retirement, is preparing for the arrival of the new incoming director, Dr. Anthony Edwardes. When a man (Gregory Peck) arrives introducing himself as Edwardes, the staff are astonished at his youth and uncharacteristic demeanor - and Petersen becomes quite taken with him.

As the two become familiar with one another, it becomes apparent something about Edwardes is off: he’s surprised by the easily-diagnosable behavior of their patients, he suffers from a bizarre fear of parallel lines on white surfaces, and (most tellingly) he doesn’t share the handwriting of the letters in his name that preceded his arrival. Petersen is the first to realize this and confronts him privately as he recovers from a very public nervous breakdown. He confides in her that he is deeply confused by what’s happening to him, but that he suffers from amnesia and believes he may have killed the real Dr. Edwardes - whose whereabouts are unaccounted for - and stolen his identity. Petersen, who recognizes her feelings for him may be clouding her professional judgement, takes it on faith that the man she’s falling in love with is innocent of murder and believes he’s instead suffering from a guilt complex that’s obfuscating what actually happened to Edwardes.

And so they go on the run, now both the targets of an intense interstate manhunt. Petersen hides him at the home of her former mentor Dr. Alex Brulov (Michael Chekhov, nephew of Anton Chekhov). After being triggered again by his peculiar phobia, Peck’s character goes into a fugue state that threatens to turn deadly for Brulov - who fortunately acts quickly to defuse the situation. Then the real work begins: Brulov begins analyzing the amnesiac and together the three solve the riddles of a recurring dream of Peck’s character (who we come to learn is named John Ballantyne).

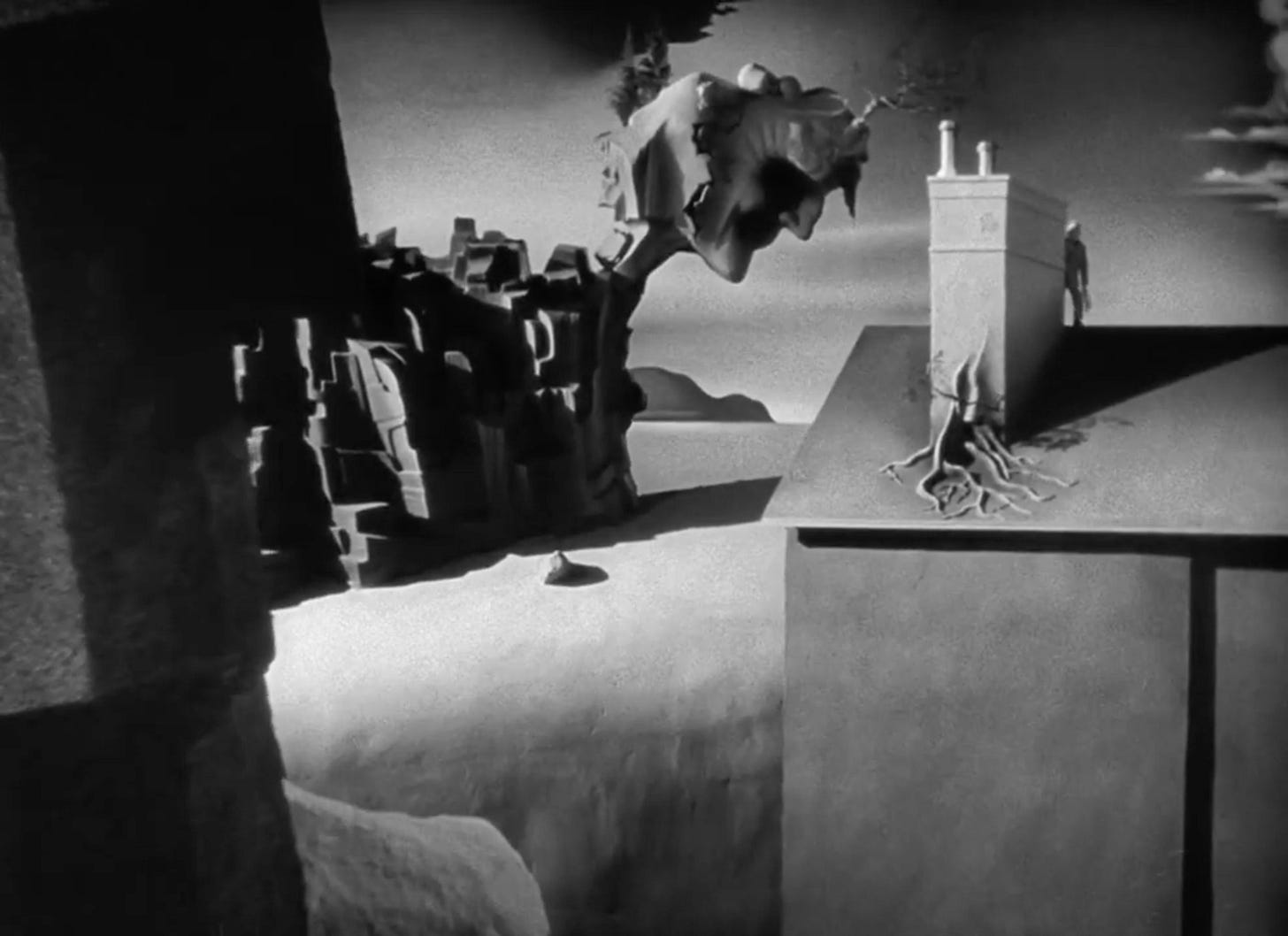

Author John Updike once described dreams as a “series of ingenious puns,” so it’s fitting that Hitchcock enlisted the help of surrealist artist Salvador Dalí - the famous conjuror of unconscious symbols with multiple meanings - to design the film’s key dream sequence. Hitchcock was adamant the dreams should be shot with “sharpness and clarity,” and not through a “blurred and hazy screen.” They are also, deliberately, not faithful reenactments of memory - as is still so often done today - but an attempt to imagine an abstract dream world. As one would expect from Dalí, his dream imagery is appropriately beguiling with giant eyeballs, distorted but familiar objects, and long shadows cast across inscrutable landscapes. (According to Donald Spoto’s Hitchcock biography, the sequence was initially conceived to occupy 20 minutes of the film’s runtime, but it proved too lengthy and complicated for Selznick or Hitchcock, and was substantially cut down as a result.)

In his essay “Hitchcock’s Spellbound: Text and Counter-Text,” critic Andrew Britton notes the images of Ballantyne’s dream “coincide point-for-point to ‘real’ events, as if they were empirical clues” pointing toward an oedipal fantasy or “psychical reality.” Ballantyne has, as Petersen correctly diagnosed, experienced a traumatic event - before Edwardes’ disappearance - that created the guilt complex causing him to think he himself killed Edwardes. But because he’s not expressly dreaming about the traumatic event itself, Ballantyne’s unable to glean meaningful information from the dream on his own; he cannot get past the events, because he cannot see them, thereby denying himself emotional convalescence. So it is up to Brulov and Petersen to find fault in his stars, as it were, by assuming the primal roles of father and mother respectively (Brulov goes as far as instructing Ballantyne to think of him as such in their first session.) And in doing so, they uncover that Ballantyne did kill someone, but crucially not Edwardes, and that another father-like figure was responsible for Edwarde’s death and Ballantyne’s framing for the crime. Once cleared, and rid of the “bad father” figure, Ballantyne would be absolved, and he and Petersen will finally be able to love freely.

An enactment of Freud’s oedipal conflict went down smoothly for audiences in 1945 because it was sublimated into a complex plot that split the family roles up so that the acts were not literal incest or patricide. But as a result, the story gets a little too complicated and the perspective shifts between Petersen (the main character) and Ballantyne (the protagonist - until the end?) can be frustrating in ways that displace gratification (Ballantyne never confronts the culprit responsible for his frame-up), and Ballantyne’s traumatic secret gets glazed over once he’s able to recall it (the flashback to it, though, is an effectively gruesome little moment). And, though it’s the precursor to those kinds of stories and not their derivation, Spellbound has the banality of a soap opera at turns, offering the kind of convenient plot resolutions that work only if you don’t think about them too hard (the culprit’s plan to frame Ballantyne takes some huge leaps of faith).

But, as always with Hitchcock, the form’s the thing - and Spellbound sees him in good form. The aforementioned dream sequence by Dalí is a highlight, as are the numerous subjective point-of-view shots - one of which comes at the very end (which I won’t spoil) and makes very little sense for whose perspective it’s from, but it’s a fun show-off moment from a filmmaker who characteristically didn’t do so without reason. The Oscar-winning musical score by Miklós Rózsa, which pioneered use of the theremin, is also inventive, if a little obtrusive at times.

Not as good as its premise suggests, Spellbound is still an interesting curio that provided Hitchcock a mine of ideas he would return to for years to come.

Spellbound, is out of print on home video and unavailable on streaming, but can be found here (at least for the moment).

Further Viewing

Dalí’s image of scissors cutting through a curtain of eyes is no doubt an allusion to the opening scene of Un Chien Andalou, in which a character (?) played by director Luis Buñuel slices open a woman’s eyeball with a razor blade. Buñuel and Dalí co-created the 1929 silent short using the surrealist principle of psychic automatism, in which no rational explanations or deliberately symbolic conceits could be employed. Its makers hoped to express ideas purely and without inhibition, the meaning of which could only be explained (if at all) by psychoanalysis. And they succeeded; the confounding imagery still startles today. You can watch Un Chien Andalou here.

Up Next

Notorious, which is available from Criterion and currently streaming on Tubi.

Cameo

Approximately 43 minutes in, Hitchcock can be seen exiting the elevator at the Empire State Hotel.

References

The Alfred Hitchcock Wiki: The Hitchcock Cameos & 1000 Frames of Hitchcock

Britton, Andrew. “Hitchcock’s Spellbound: Text and Counter-Text”. Cine-Action!, Winter 1986.

Spoto, Donald. The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock. United States, Da Capo Press, 1999.

Truffaut, Francois. Hitchcock. United States, Simon & Schuster, 1985.